The political landscape in Ethiopia has been significantly influenced by the country’s loss of port access, following Eritrea’s declaration of independence in 1993 and the subsequent Ethiopia-Eritrea war in 1998. Prior to 1993, Eritrea was an integrated federal entity within Ethiopia, granting Ethiopia vital access to the Red Sea. This access was particularly crucial at the Assab port in southeastern Eritrea, which facilitated approximately 70% of Ethiopia’s foreign trade. Initially, post-independence relations between Ethiopia and Eritrea remained cordial, allowing Ethiopia to continue utilizing Eritrean ports. However, this dynamic drastically changed with the onset of the 1998 war over the contested Badme border area.

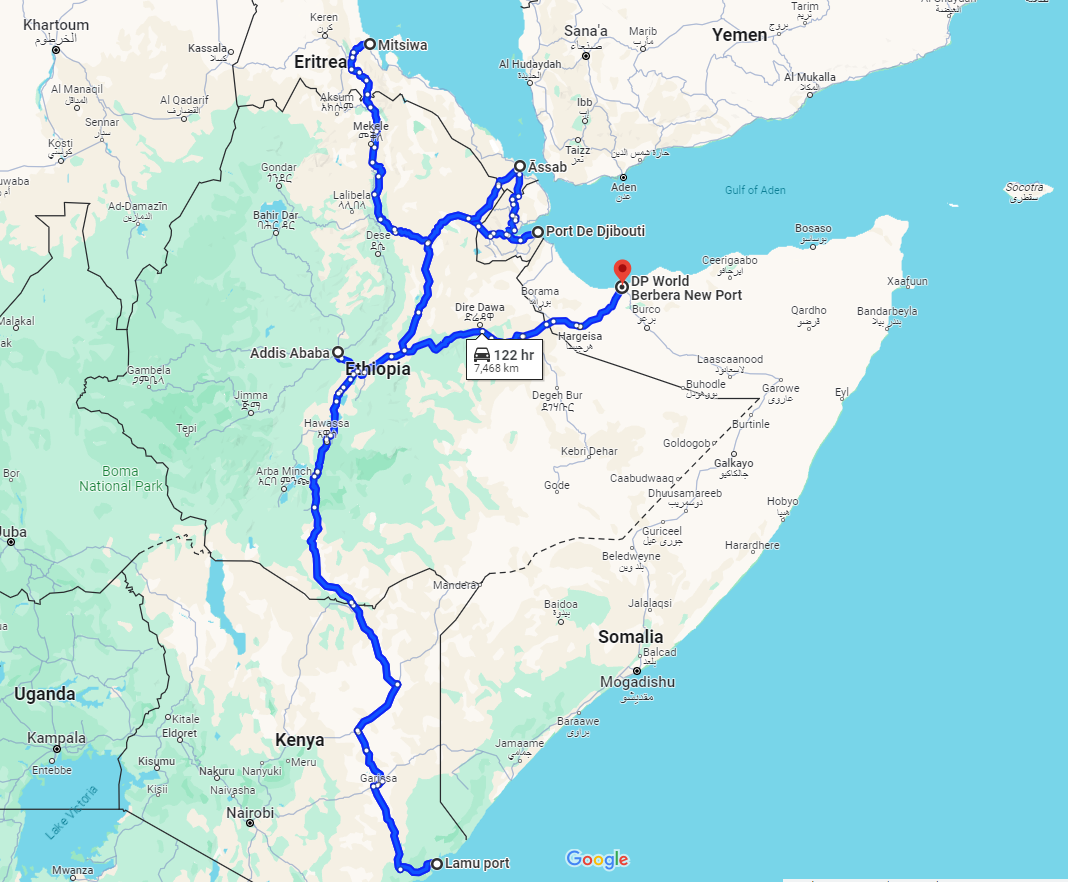

The conflict severely damaged diplomatic ties, leading to Eritrea revoking Ethiopia’s port privileges and effectively rendering Ethiopia landlocked. Ethiopia currently relies heavily on the Port of Djibouti, which handles over 90% of its foreign trade. This reliance comes at a significant cost, with Ethiopia spending around $1.5 billion annually in port fees. Despite its necessity, this dependency on Djibouti’s port is far from ideal from Ethiopia’s perspective. Ethiopia has recognized a key vulnerability in the main A1 Motorway, which connects the country’s Afar region to the Port of Djibouti and extends to Addis Ababa, the capital. This route’s strategic importance is underscored by the fact that any blockade or disruption, especially in times of conflict, could immediately cut off Ethiopia’s access to essential imports. This vulnerability was starkly highlighted during the internal conflict in the Tigray region from 2020 to November 2022, when disruptions in this corridor exposed Ethiopia to significant logistical and economic challenges.

On October 13th, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed made a bold assertion regarding his country’s position in relation to the Red Sea. He argued that the Red Sea should be considered Ethiopia’s natural boundary, stressing the necessity for Ethiopia to secure a port along this sea to escape what he termed a “geographic prison.” This statement was not well-received by Ethiopia’s Red Sea neighbors, including Eritrea, Djibouti, and Somalia.

In a televised speech, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed articulated his belief that Ethiopia was confined by its geographic limitations, and the solution lay in establishing a port on the Red Sea. To substantiate his claim, he referenced the 19th-century General Ras Alula, who regarded the Red Sea as Ethiopia’s rightful boundary. In a subsequent broadcast, Abiy presented maps of third-century kingdoms, which he interpreted as evidence of Ethiopia’s historical claim to the adjacent coastline. Abiy’s rhetoric took a more ominous tone when he suggested that Ethiopia’s lack of port access might be a catalyst for future conflicts. This warning was underscored by a significant show of military strength—a parade in the capital, Addis Ababa. The head of the Ethiopian Air Force underscored this message, instructing troops to prepare for potential warfare. Following these events, satellite imagery reportedly captured troop movements along the Ethiopia-Eritrea border, further escalating tensions in the region.

Abiy Ahmed, who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019 for his efforts in resolving the border conflict with Eritrea, has recently shifted his focus to securing port access from the same country, even hinting at the possibility of conflict. This marks a significant change in approach for a leader previously celebrated for his peace-making initiatives. When Abiy ascended to power in Ethiopia in 2018, he promptly signed a peace agreement with Isaias Afwerki, Eritrea’s leader. This agreement was mutually beneficial for both leaders, as it served to suppress the influence of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), which had dominated Ethiopian politics for nearly three decades. After being ousted from power in Addis Ababa by Abiy, the TPLF retreated to the Tigray region, finding themselves encircled by Ethiopian federal forces to the south and the Eritrean army to the north.

The civil war that erupted in late 2020 between Abiy’s federal forces and the TPLF saw the Eritrean army siding with Abiy. This conflict was marked by severe human rights violations committed by both sides. Eritrea’s support played a crucial role in enabling Abiy to maintain his hold on power in Ethiopia. However, the relationship between Abiy and Afwerki has recently deteriorated. The strain primarily arose from Abiy’s decision to sign a peace deal with the TPLF in late 2022, an action perceived by Afwerki as a betrayal. This tension was exacerbated by Ethiopia’s failure to consult Eritrea during the peace negotiations with the TPLF, and the continued presence of the TPLF government in power. This turn of events suggests a complex and evolving political landscape in the Horn of Africa, marked by shifting alliances and ongoing tensions.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, in response to Ethiopia’s landlocked status and its associated economic challenges, has been actively seeking access to additional Red Sea ports. His government is currently working on developing a transport corridor to the Lamu port in Kenya. However, the Lamu transport corridor project is still in its initial stages and has faced multiple delays, exacerbating Ethiopia’s accessibility issues.

Abiy’s concerns about Ethiopia’s lack of direct sea access have become increasingly evident, leading him to apply pressure on neighboring countries in a bid to secure maritime trade routes. In support of his argument, he references United Nations studies which suggest that the absence of sea access can reduce a nation’s GDP by up to 20%. This statistic underlines the significant economic disadvantage faced by landlocked countries. Ethiopia primarily depends on Djibouti for sea access, a reliance that incurs substantial costs—over a billion dollars annually. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has declared this situation unsustainable and is advocating for his country to gain independent port access. The economic rationale behind this strategy carries considerable weight, highlighting the critical importance of maritime trade and access in bolstering a nation’s economic stability and growth.

The approach taken by Ethiopia under Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, aimed at securing maritime access, raises significant concerns about regional stability. Instead of fostering mutual trust and economic cooperation, the Prime Minister’s tactics appear to be steering the region towards a militaristic outlook. This shift seems to overlook a fundamental principle: that conflict is generally detrimental to economic prosperity.

Since assuming power, Ethiopia under Abiy Ahmed has been involved in several conflicts. The country has experienced two wars in the Tigray region, along with ongoing insurgencies in the Amhara region. These conflicts have had devastating humanitarian consequences, resulting in hundreds of thousands of deaths and the displacement of nearly a million people. Engaging in a third conflict with a neighboring country could have catastrophic effects, not just for Ethiopia, but for the Horn of Africa region as a whole.

Escalating tensions, particularly over access to a port, could significantly impact the entire region. Such a scenario risks not only further instability but could also impede crucial trade routes, affecting the economic health of neighboring countries. Ethiopia’s current strategy, therefore, raises serious questions about the balance between achieving national objectives and maintaining regional peace and economic stability.